-

Backed by 30 years

of science

-

Developed by

microbiome experts

-

UK's #1 Manufacturer

-

Friendly bacteria

for every life stage

Gut support, for every life stage

At ProVen Biotics, we know that maintaining a balanced gut microbiome is essential for you and your family’s overall wellness. That is why we have our own team of leading research scientists and state-of-the-art manufacturing capabilities developing gut health supplements tailored to suit every stage of life.

Our carefully formulated gut health supplements incorporate our extensively researched and award-winning live friendly bacteria blends to support your gut balance and overall health. Our unique, proprietary bacteria blends combine Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria strains with other key live cultures and a wide range of nutrients in products that support the whole family.

We have products for babies and children, adults and those aged 50 plus, and we have also developed products for specific needs - for women of all ages, gut health support for travel, immunity, and for support alongside and following antibiotics.

-

-

-

-

-

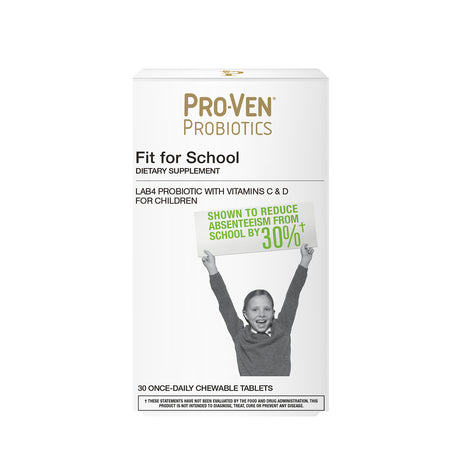

Friendly bacteria with vitamin C for children

$19.95Unit price /Unavailable -

-

-

-

-

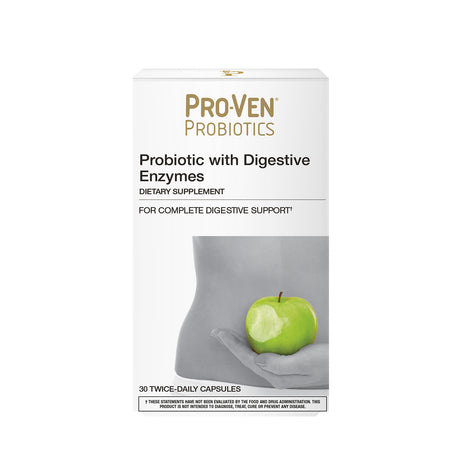

Probiotic with Digestive Enzymes

Complete supplementation in one pack

$24.95Unit price /Unavailable -

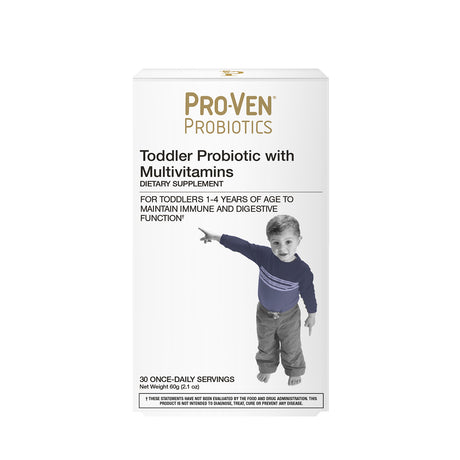

Toddler Probiotic with Multivitamins

Multivitamins and prebiotic fibre for toddlers 12 months - 4 years

$19.95Unit price /Unavailable -

Total Intestinal & Digestive Support

High in fibre, L-Glutamine, prebiotics & vitamins A.C,D

$29.95Unit price /Unavailable

-

Specially formulated for all areas of female health, our ProVen product formulations and bundles offer specific gut health support for women at all ages and stages of life, including pregnancy and menopause.

Discover range -

At ProVen Probiotics, we aim to support the health and digestion of the whole family and our range includes high-strength live bacteria designed to support men every day, whatever their lifestyle or need.

Discover range -

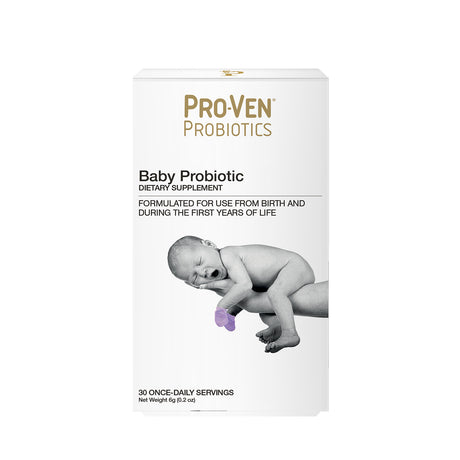

Whether your baby is breast fed or formula fed, we have a product to support their microbiome development in their first years of life – from newborn to toddler.

Discover range -

Our products for kids have been specifically developed to provide effective everyday support for children aged 4-16 – sugar-free chewable tablets and stick packs for easy daily use.

Discover range -

Collection

Discover range -

Collection

Discover range -

Our Urgent-C range has been developed with high-dose vitamin C and a range of other immune supporting nutrients as well as our award-winning ProVen friendly bacteria – for daily and intensive use.

Discover range -

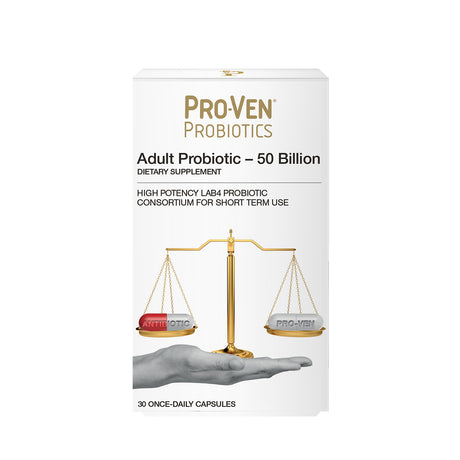

Stay healthy on-the-go with our travel-friendly live bacteria product, formulated with additional nutrients specifically for use when travelling – by plane, train or car, within the UK or abroad.

Discover range -

For overall health with the added benefit of 2.5 billion live ProVen bacteria, our A-Z multivitamin range includes formulations specifically developed for kids, adults and ages 50+.

Discover range

What makes ProVen Probiotics different?

-

35+ Clinical Trials

Our bacteria blends are supported by more than 35 clinical human research studies and over 100 articles, research papers and posters. We have a large team of research scientists dedicated to understanding the efficacy and effectiveness of our strains across an ever-growing number of contexts and identifying opportunities for new product development.

-

Unique Lab4 Blends

We use our proprietary live bacteria blends, known as Lab4, Lab4B, Lab4P and Lab4S, in our products. Each multi-strain consortium has been extensively tested and studied to ensure efficacy and applicability in product manufacture. With ‘start to finish’ manufacturing capabilities, we manage our production process from strain fermentation and blend formulation to finished products.

-

20+ Countries Worldwide

ProVen Biotics products are sold in more than 20 countries around the world, including the UK, Ireland, South Africa, China, Hong Kong, Spain and the USA. All products are manufactured at our state-of-the-art cGMP certified and fully integrated facility in the UK and distributed to our partners and operations around the world.

-

Established 10+ Years

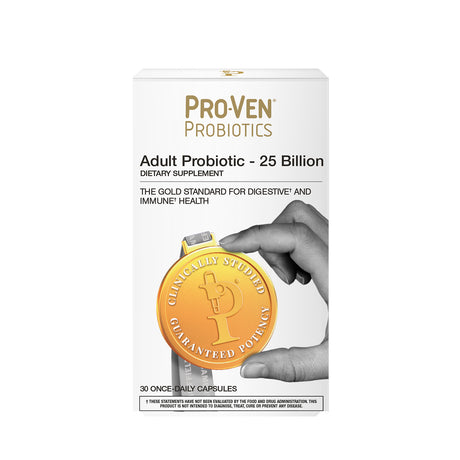

The ProVen Biotics brand was launched in 2012 with our flagship Adult 25 Billion friendly bacteria supplement, and the range has since grown to more than 25 products developed to support every life stage and specific needs. We develop products based upon our own studies and understanding of the latest developments in microbiome research.

Testimonials

“My stomach has never felt so 'normal' my IBS is under control, no bloating and no more stomach pain.”

REVIEWING 50 BILLION- SHAPELINE

My kids just love this product for my pickyeater. Keeps her immune system boosted. Normally we have absent days in the first half term after summer and this year we got 100% attendance!

REVIEWING PROVEN

Great products great value. Been using this brand for few years

REVIEWING PROVEN